Economist Profiles

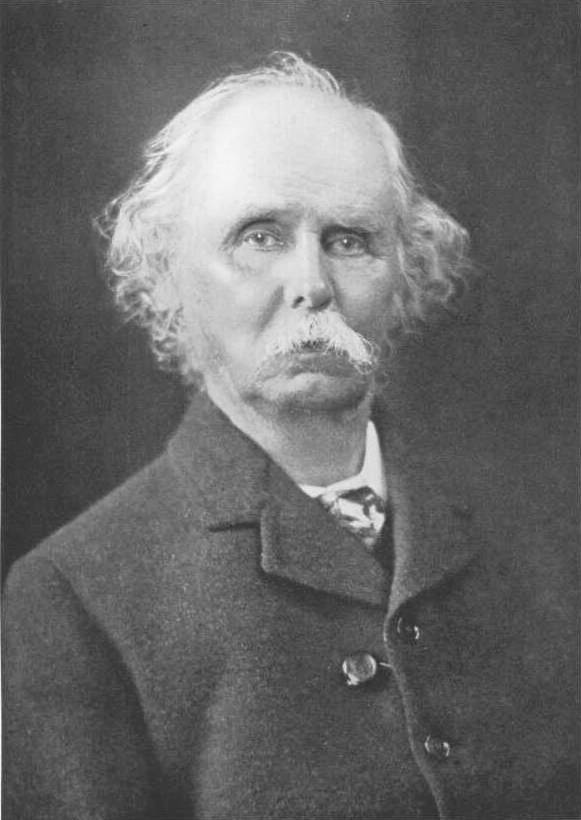

Alfred Marshall

Read a summary or generate practice questions using the INOMICS AI tool

Alfred Marshall is a famous economist who made great contributions to the field when it was still relatively new towards the end of the 19th century. Yet, students often learn about important figures in economics only briefly and in passing, although the content taught in economics courses often comes from brilliant economists such as Marshall.

Indeed, Alfred Marshall is considered one of the founding thinkers of neoclassical economics. He was a mathematician and philosopher who later became a microeconomist. His work formalized foundational economic concepts and theories such as supply and demand, price elasticity of demand, consumer and producer surplus, marginal utility, and production costs to produce some of the earliest cohesive economic models.

He was even instrumental in making economics its own separate subject for the very first time at Cambridge, where he taught for much of his career. The entire field of economics was greatly influenced by both Marshall and several of his pupils, including famous economists Arthur Pigou and John Maynard Keynes.

Alfred Marshall’s life

Marshall was born in 1842 in London, England. He was at one time considering a career in the clergy, but abandoned the idea after he demonstrated significant talent for mathematics. Thereafter, Marshall attended St. John’s College in Cambridge, earning accolades in math (such as “Second Wrangler” in the Cambridge Mathematical Tripos) and securing his future as an academic.

At first, Marshall wasn’t an economist – few in his time were! Rather, he studied subjects like math, physics, philosophy, and ethics, like many other thinkers of his time. It was allegedly Marshall’s love for ethics that led him to eventually study economic decision-making, as he saw economics as a means of improving the human condition for the common man. This was an ideal he shared with Adam Smith, another (earlier) important British thinker in economics.

Thus, Marshall lent his considerable intellect to economic pursuits. In 1865, he was elected to a fellowship at St. John’s College at Cambridge. He married in 1877, left St. John’s, and taught at the University of Bristol and then at Oxford for a period afterward. In 1885, he became the Professor of Political Economy at the University of Cambridge, where he remained until his retirement in 1908.

Image credit: Pixabay.

During this time, Marshall turned the study of economics into its own, self-contained discipline, creating the Faculty of Economics and Politics and helping to launch the first formal economics degree program at Cambridge in 1903. Famously, Marshall taught economic giants Arthur C. Pigou and John Maynard Keynes, who each went on to make their own grand contributions to the field, and often had great things to say about Marshall’s influence and teaching.

The book Principles of Economics was Alfred Marshall’s magnum opus. He worked on it from 1881 to 1890. It was rapidly recognized as a success and a great achievement in economics upon its publishing. Yet Marshall was unsatisfied with the limiting assumptions of classical economics (some of which he helped to popularize!), so his work shouldn’t be viewed as a definitive snapshot of his economic beliefs.

Instead, Marshall was keen to have his students surpass him and replace his models with more accurate ones, such that he was known to gift them copies of his Principles of Economics with signed messages such as ‘To [name], in the hope that in due course [they] will render this treatise obsolete’.

Alfred Marshall died in Cambridge in 1924, at the age of 81.

Alfred Marshall’s contributions to economics

Marshall’s contributions to economics are numerous. As a former mathematician, he formulated many concepts in the field with equations. This approach helped him formally define many of the concepts mentioned at the beginning of this article, which other economists of his time had not been able to do.

Nevertheless, he also attempted to distill economic insights into language that was understandable by non-mathematicians, a crucial skill for successful economists even in today’s world. This is evidenced by his placing math equations and graphs only in the footnotes and appendices of his Principles of Economics, not the main text.

Besides Principles of Economics, Marshall’s other economics works include the 1879 text The Economics of Industry, which he co-wrote with his wife Mary Paley (a former student of his, and one of the first-ever female economics students. She was denied a degree on the basis of being a woman, a discriminatory policy that her husband Alfred Marshall supported; but nevertheless she was a brilliant economist in her own right).

Image credit: Pixabay.

Alfred Marshall was also a crucial figure in popularizing the idea of “thinking on the margin”. Marginal analysis today is a core and foundational concept in economics, where someone’s decision is based on the benefit that the next unit provides, not the sum total of all units. The so-called “Marginal Revolution” began with economists William Jevons, Carl Menger, and Léon Walras in the 1870s.

Marshall is one of a “second wave” of economists who, seeing the brilliance of these marginal ideas, set about integrating them into economic models. John Keynes, his former student, said this of his work: “[William] Jevons saw the kettle boil and called out with the delighted voice of a child; Marshall too had seen the kettle boil and sat down silently to build an engine.”

According to Keynes, Marshall’s writing also put an end to a debate over whether cost or demand determined the value of items in a market, positing convincingly that it was actually both. As such, Marshall is credited with developing the idea that the price and output supplied of a good are determined by the intersection of supply and demand. This approach is so foundational as to seem obvious to economists today, which speaks to the success of his idea!

Marshall also introduced early ideas of the different “time horizons” that economists frequently reference. He pointed out that in the short run, changes in demand tend to have more effects on markets than costs, while in the long run supply-side facts like costs can significantly shape markets. According to Keynes, Marshall was also the first to provide an actual formula for price elasticity of demand – which earlier authors had mentioned, but not formalized. He did the same with consumer and producer surplus as well, which French engineer and later self-taught economist Jules Dupuit had originally described.

Marshall’s works were broad, covering even more topics than these. His students Keynes and Pigou, and later economists like Joseph Schumpeter, have several recorded quotes about the thoroughness of Marshall’s Principles that are readily available online. These include the fact that Marshall’s models and formulae hidden in the footnotes of the Principles often provided solutions to problems that were only thought of later on.

So, next time you’re studying economics – particularly microeconomics topics – don’t be surprised to hear Alfred Marshall being given the credit!

References

1 https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/bios/Marshall.html

2 https://carleton.ca/keirarmstrong/learning-resources/selected-biographies/marshall-alfred-1842-1924/

3 https://hope.econ.duke.edu/sites/hope.econ.duke.edu/files/documents/caldwell_2004_ALFRED%20MARSHALL%20and%20the%20CAMBRIDGE%20SCHOOL_0.pdf

Header image credit: public domain.

-

- Postdoc Job

- Posted 4 months ago

Postdoctoral Program

At King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center (KAPSARC) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

-

- Conference

- (Partially Online)

- Posted 1 month ago

Annual Research Conference 2024

Between 21 Nov and 22 Nov in Ispra, Italy

-

- Conference

- Posted 1 month ago

2024 International Conference on Finance for the Common Good

Between 8 Aug and 10 Aug in Dayton, United States